Subscribe by Email

-

Recent Posts

Monthly Archives: May 2009

Journalism Above the Fold

New York Times foreign correspondent Dexter Filkins’s essay “Surging and Awakening” in The New Republic on the turnabout of U.S. strategy in Iraq and what it could mean in Afghanistan shouldn’t be missed. Filkins delivered a whopper of a book (“The Forever War”) on U.S. involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan in September 2008, which won a Pulitzer Prize, proving he’s a reporter to follow.

Christopher Goffard’s front-page article “Fleeing All but Each Other” in The Los Angeles Times on the young drifters and runaways who crisscross the country by hopping trains was riveting reading. I could not put down its tragic story of Adam Kuntz and Ashley Hughes and the hard lives of such “traveling kids.”

Vanity Fair’s June article “Hello, Madoff!” on what the Ponzi schemer’s secretary of 20 years witnessed is essential reading, especially for those still trying to figure out how this all happened and what this nutcase was like.

Edward Klein’s book excerpt “The Lion and Legacy” on Ted Kennedy’s battle with brain cancer in the June Vanity Fair is a tough look behind the dilemma. And among other things, it claims Caroline Kennedy pulled out of last year’s N.Y. Senate race because of her kids’ concerns, which she has since dismissed as untrue.

Writer Daphne Merkin’s lifelong battle with chronic depression is heart-wrenchingly captured in her article “A Long Journey in the Dark” in the New York Times Magazine. It’s a tough read but can’t be missed for those hoping she’ll continue to recover. Continue reading

Posted in Articles

Leave a comment

People of the Book

The follow-up to the Pulitzer Prize winner’s book “March” in 2006, “People of the Book” is another of Geraldine Brooks’s intricately woven historical novels. In it, Brooks spins a fictional tale based on the spare details known about the real-life medieval artifact, the Sarajevo Haggadah, one of the oldest Jewish illuminated texts, whose survival through centuries of wars and purges seems nothing short of “a series of miracles.”

It’s narrated in part by Hanna, a rare book conservator hired in 1996 by the United Nations to inspect and restore the ancient Haggadah so it can be put on exhibit. Under examination, Hanna finds various clues in the book to its history, whereabouts and guardians, including an insect’s wing, wine stains, a white hair and salt crystals.

As Hanna pursues unraveling these mysteries, alternate chapters of the novel flash back to various points in the Haggadah’s history and those who possessed it during such turbulent times as: Sarajevo 1940, Vienna 1894, Venice 1609, Tarragona 1492 and Seville 1480. “Inquisition, Nazis, extremist Serb nationalists … the book at this point bears witness to all that,” says one of Hanna’s colleagues.

Indeed, yet the Sarajevo Haggadah also bears witness to those of various faiths who risked their lives to save it from destruction: including a Muslim, Dervis Korbut (his real name), who saved it from the Nazis in 1941; a Catholic priest, Vistorini, who spared its burning during the Inquisition around 1609; and another Muslim, Enver Imamovic (his real name), who hid it in a bank vault during the Bosnian War of the 1990s.

The flashback chapters are consistently rich in detail of the eras and lives of those who heralded the Haggadah. For the most part, the novel is a suspenseful, at times harrowing read, retracing the persecution of the Jews and the Haggadah’s many close calls, as well as Hanna’s contemporary challenges as its conservator. It seems a faster moving novel than Brooks’s “March,” with a bit more to it as well. Only at times does Brooks’s elaborate story lose readers among its many characters and eras, with some abrupt transitions requiring readers to stay quite focused. It’s not exactly your airhead beach read. It packs a lot in in the span of a few hundred pages.

Only in a couple instances did I think that Brooks was stretching it a bit to become a Jewish type of “Da Vinci Code” thriller. Mostly, “People of the Book” doesn’t get that crazy. Despite occasional quirks, Brooks weaves a memorable Sarajevo Haggadah story that stays true to its source.

ps. Apparently Catherine Zeta Jones has acquired the film rights to “People of the Book.” But how you make a film out of it, is anyone’s guess. Continue reading

Posted in Books

Leave a comment

Fighting

The movie “Fighting” is likable in a small-film-kind-of way. It’s not great, nor perhaps the most believable of plots, but it is still entertaining and attention drawing. It involves 20-something Shawn MacArthur (Channing Tatum) from Alabama who lives in N.Y.C. selling wares on the street until he bumps into hustler Harvey Boarden (Terrence Howard) who introduces him into the underground world of fight clubs as a way of making money. If you’re expecting “Fight Club,” from 1999, you’ll be a bit disappointed. It’s not exactly like that, nor does it have as creative a screenplay, or feature as many fights. In fact, there’s only four in “Fighting.” But they seem pretty good. The actor, Channing Tatum, apparently broke his nose filming one of the fight scenes. So the sequences seem fairly realistic and suspenseful, but not overly scary. The film, after all, is rated PG-13, not R. Terrence Howard is quite good in his role as the kid’s fight manager. And Tatum, whose career seems to be on the rise, looks just fine as the hunky Alabama brawler with a troubled past. There are some nice shots of N.Y.C. (though mostly skyline types) and an upbeat soundtrack that keeps things moving. The filming is not perfect (the boom microphone appears in at least one of the scenes at the top of the screen), but by the end, “Fighting” does manage to throw a small, enjoyable punch. Continue reading

Posted in Movies

Leave a comment

State of Play

The political thriller “State of Play” couldn’t be missed for its journalism perspective and its shots of D.C. And come on, a cast of Russell Crowe, Helen Mirren, Jeff Daniels, Ben Affleck, Robin Wright Penn – it couldn’t be too bad right? A pudgy (okay fat) Russell Crowe plays Cal McAffrey, an old-school print reporter who teams up with online rookie columnist Della Frye (Rachel McAdams) to cover a string of murders, including the death of a congressman’s mistress. So far so good, but as time goes on, the plot gets wackily convoluted and preposterous amid scenes of corruption, mercenaries for hire, and cover-up, not to mention those having a conflict of interest for Cal in reporting on his old college pal, Congressman Stephen Collins (played by Affleck). Pretty soon you just have to go with “State of Play,” crazy or not, and enjoy it for what you can. Its angle on the newspaper biz remains interesting for those nostalgic for the heyday of print journalism. Perhaps Ann Hornaday of The Washington Post touched on that best, when she wrote:

“State of Play’s” final montage, a loving valentine to old-fashioned newspapering with its clanging presses … plays like a sepia-toned anthropological documentary about a vanishing indigenous people. But, at least for members of that bloodied and battered tribe, it’s impossible not to be touched. In some distant future, when newsprint has long disappeared and people get their news and movies by way of a biologically embedded chip, at least they’ll know that attention, once, was paid. On behalf of ink-stained wretches everywhere: Thanks for caring, guys!” Continue reading

Posted in Movies

Leave a comment

Revolutionary Road

Good thing the movie came out or I might never have read this dark and brilliant, 1961 novel by Richard Yates, about a couple whose lives derail amid the 1950’s suburbs. The book takes a wry, satirical look at the conformity of the times and the American dream, and reminded me a bit of the same disillusioned 1950s of J.D. Salinger’s books or perhaps Sylvia Plath’s.

It involves Frank and April Wheeler trying to stay above “the larger absurdities of deadly dull jobs in the city and deadly dull homes in the suburbs.” And yet they’re caught amid the “hopeless, emptiness” of it, wherein Frank works at a job he hates at “Knox Business Machines” and April takes care of the kids and their house at the end of Revolutionary Road.

But then, April hatches a plan to move the family in the fall to Paris, where she can work and Frank can find out what he really wants to do. And for a while the plan (deemed by colleagues and neighbors as selfish and unrealistic) causes a time of “such joyous derangement, such exultant carelessness that Frank Wheeler could never afterwards remember how long it lasted.” In the end though, events conspire, the Wheelers change their minds, and the plan and everything comes crashing down.

It’s a bleak ending of a couple on the brink. With an honest mirror on American middle-class suburbia, the book stands the test of time, and its characters and descriptions seem amusingly on target. There are the annoying neighbors, Shep and Milly Campbell; Frank’s mistress from work, Maureen Gruber; the busybody real estate agent Mrs. Givings; and her son John, who’s in a mental institution despite seeming to be the only one to speak the truth. But the best characters are Frank and April Wheeler, whose portraits are both troubling and at times darkly humorous.

“Listen a minute. I won’t touch you. I just want to say I’m sorry.”

“That’s wonderful. Now will you please leave me alone?” Continue reading

Posted in Books

2 Comments

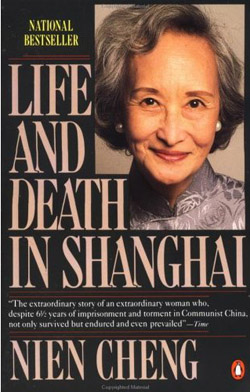

Tea With Nien Cheng

“The past is forever with me and I remember it all now,” starts Nien Cheng’s gripping account of her life during China’s Cultural Revolution. Though published in 1987, “Life and Death in Shanghai” is still as potent a read as ever. In it, Cheng recounts how the Red Guards ransacked her house in Shanghai in 1966 and put her in prison for 6½ years in solitary confinement for being a “class enemy and running dog of the imperialists.” Widowed at the time and living with her daughter, Cheng worked at Shell Oil till the Maoists closed its Shanghai office. In the book, Cheng describes the harsh interrogations and tactics used in prison in attempts to make her confess (falsely) to being a “spy.” But despite torture and deteriorating health, she never does. She remains vigilant in refuting the Maoist revolutionaries’ accusations and survives till her release, only to find out after, tragically, that revolutionaries had killed her daughter. She forges a plan to leave China, which she does in 1980 at the age of 65 with just one suitcase and $20, eventually settling in Washington, D.C., where she has lived since 1983.

Her book is a compelling survivor’s memoir that includes a fair share of informative historical and political context on the Cultural Revolution. I found it an extraordinary story of a courageous woman, who I had the great fortune to meet for tea early in April 2009. She greeted me at the lobby of her condo building and appeared quite younger than her 94 years. She was very gracious, warmhearted and open.

We made the trek to her floor and she seemed fine, though slowed she said by the arthritis where the Communists had beaten her. There for four hours, she spoke of her life, the Communist government, the book and subjects that came to her, and I mainly listened not wanting to move or interrupt. She was quite amazing, her mind and memory were sharp and I realized, as her book’s first line states, that indeed she “remembers it all.”

She made references to life during the Sino-Japanese War (1937-1941); listening to Winston Churchill on the radio when she attended London’s School of Economics as the first Chinese woman; living in Australia as a Chinese diplomat’s wife during the attack on Pearl Harbor; surviving life under Mao; and attending a White House State Dinner at the Reagans’ request after her book was published in 1987.

Indeed, hers is a remarkable 20th-century life. And yet she talked about it very modestly, and chalked up the book’s success solely to timing. When it was published she said there wasn’t much on the Cultural Revolution; it was still not widely written about. Her book she said took about two years to write upon her arrival in D.C. in 1983, which she did on a manual typewriter, and a third of which she left on the cutting-room floor. I asked her why she hadn’t written another book after her first had become a bestseller, and she said back then she still feared Chinese reprisal. But she laughed when she said her book had sold well for a while in China before the Communists found out and banned it. She had been back to Hong Kong but said she wouldn’t go back to mainland China.

“I can forgive them for imprisoning me,” she said, “but I can’t forgive them for murdering my daughter. … I never found out who killed her, the Communists just wanted to cover it up.” The loss of her daughter is with her everyday, and she feels guilty, she says, for having been the one to have lived. And yet, what she’s left readers is an invaluable life and look at Maoist China. Continue reading

Posted in Books

3 Comments

The Reader

The Bernhard Schlink story, from which Kate Winslet received a best actress Oscar and which has also garnered sharp criticism, recounts a 15-year-old boy’s relationship with a woman twice his age, whom he finds out years later when she’s put on trial, was a Nazi guard during the war. The woman (Hanna), he learns, joined the Nazis to avoid a job promotion and to keep secret her life of shame as an illiterate. The boy (Michael), who narrates as an adult, never overcomes his passion and memories of Hanna and his shame and guilt over it. “I wanted simultaneously to understand Hanna’s crime and to condemn it. … But it was impossible to do both.” He attends her trial and visits a former concentration camp to try to come to grips with her Nazi past. But he doesn’t tell the judge when he discovers she’s illiterate and her defense is marred. Ultimately, she’s found guilty in the deaths of 300 Holocaust victims burned in a church and is sentenced to life in prison, where Michael later sends her audiotapes, and over time, she learns to read. The ending that follows is not exactly expected, but yet, not out of place either amid the dark subject matter.

People seem to be either moved by this story for its moral complexity and themes of love, guilt, shame and horror regarding the Holocaust, or to hate it as revisionist, exculpatory drivel with an empathetic depiction of Hanna and a metaphor of illiteracy that serves to absolve Nazi-era Germans of their knowledge of, or complicity in, the Holocaust. It’s a view of a war criminal’s perspective that can’t help but be dicey. Also the story’s nudity and eroticism, especially in the film, have been ridiculed as gratuitous and exploitive. I think it’s an intense read (and film) that raises disturbing questions. But it’s best you decide. Continue reading